Pounds, shillings, and pence… oh my!

I like to give my students a deep dive into the 18th Century, and teaching about colonial money is the perfect way to add another layer of interest and excitement to my social studies instruction.

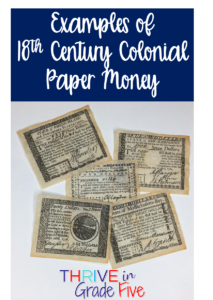

Each of the 13 Colonies operated like its own country. Because of this, each colony printed its own paper money. These paper bills are fascinating to look at and study. I spend a little time teaching about paper money, and these pieces of currency are a rich primary source.

There were many different types of currency, bartering, and credit used in the colonies. However, all of the colonies subscribed to the pounds, shillings, and pence system. So, this is the system that I teach my students.

How did pounds, shillings, and pence work?

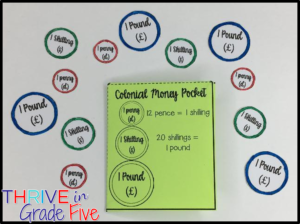

First, students need to understand the conversion rate among pounds, shillings, and pence.

I write the following information on the board and we complete a few practice questions together.

12 pence = 1 shilling

20 shillings = 1 pound

Practice Questions:

- Mary has 25 shillings. Please simplify the amount of money she has. Answer: She has one pound and five shillings.

- Brighton has 25 pence. Please simplify the amount of money he has. Answer: He has two shillings and one penny.

- Tom has 35 shillings. Please simplify the amount of money he has. Answer: He has one pound and fifteen shillings.

How to Write Pounds, Shillings, and Pence

It’s fairly simple to write these money amounts!

Place the pound sign in front and then separate the pounds, shillings, and pence values with periods.

Example: Three pounds, six shillings, and eleven pence would be written as: £ 3 . 6 . 11

Practice:

- Write twelve pounds, eight shillings, and three pence

- Write ten pounds, fifteen shillings, and ten pence

- Write one hundred pounds, nineteen shillings, and five pence

It is helpful for my students to make a Colonial Money Pocket. This simple envelope with pounds, shillings, and pence gives a good visual representation of the conversion rate and 18th Century money amounts.

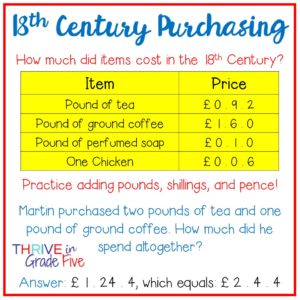

Next, we practice adding pounds, shillings, and pence.

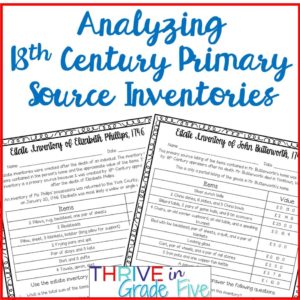

Finally, once students have a firm understanding of 18th Century money, we analyze 18th Century Primary Source Estate Inventories.

Estate inventories are a rich primary source. Not only can we learn about the monetary values of items, we can also learn about how colonists lived and what possessions were valuable to them.

An Unfortunate Truth About Colonial Money

If you’ve studied 18th Century colonial history, you know that it was common practice to place monetary value on the lives of enslaved individuals.

You must use your best judgment when deciding whether or not to introduce the concept of monetary value placed on enslaved individuals.

I’ve been teaching social studies in Title I, highly diverse schools for years. Some of my student groups are mature, receptive, and genuinely want to learn about all aspects of the 18th Century.

In some of my groups, however, I would never introduce this concept. It’s truly all about knowing your students and what they are mature enough to handle.

A few years ago, I attended a workshop in Boston focusing on the 18th Century. The presenter gave us a primary source inventory for a wealthy man that listed the names and monetary values of enslaved individuals.

While we were examining the inventory, the presenter pointed out that enslaved female, Old Dinah, had a monetary value listed as one shilling. The value of a pound of butter at the time was around one shilling.

Appraisers listed Old Dinah’s value as about the same as a pound of butter.

This realization pierced me right through the heart. How could a person say that a human being’s life is worth a pound of butter?

Just talking about this one instance is enough for students to have a deeper understanding of the cruelty of slavery.

This complete mini-unit on 18th Century Colonial Money is just what you need to teach this fascinating aspect of early American history. Check it out here: 18th Century Colonial Money Mini-Unit.

P.S. I have a freebie just for you! Please enter your first name and email address to have a free resource, 18th Century Colonial Money: A Primary Source Investigation, emailed directly to you.

2 Comments

This is the second year I do read aloud Blood on the River and it takes a long time to get thru it. Now my kids love it, but it puts us way behind. I have a bilingual class and so our time is only 30 minutes daily for SS. I have thought about abandoning the read aloud and just summarize and go on. What do you suggest?

I would definitely summarize the read aloud and move on. Having only 30 minutes per day is really hard for social studies. Save time wherever you can!