Slavery is an uncomfortable, quite painful topic to teach. The first mention of enslaved individuals often occurs in upper elementary social studies.

Many teachers are understandably hesitant to teach the topic of slavery and either gloss over it or skip this part of our history entirely.

Our students deserve to know the full story of our past, including the shameful parts.

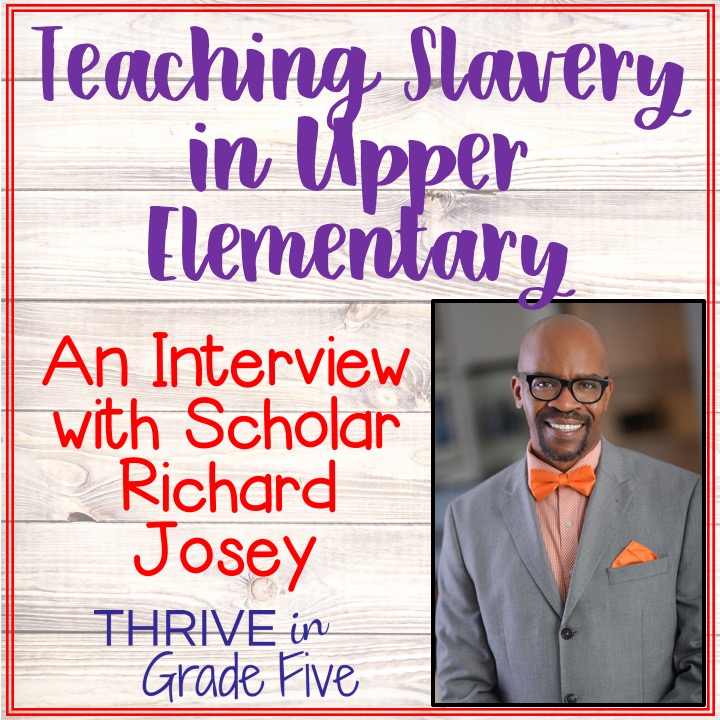

I had the honor of meeting an amazing, knowledgeable scholar, Richard Josey, during a teacher’s institute at George Washington’s Mount Vernon. He graciously agreed to an interview on this topic because one of his passions is helping educators teach this sensitive topic accurately and responsibly.

When teaching upper elementary (4th-6th grade) social studies, many teachers skip over the topic of slavery because it’s uncomfortable and painful to teach. Why do you think it’s important to teach about slavery to this age group as part of our nation’s history?

Fourth, fifth, and sixth graders are a point where they are beginning to develop the ability to understand different points of view.

This is a perfect time for them to discover differing and conflicting perspectives surrounding slavery. It’s complicated. It’s nuanced. It’s uncomfortable and painful. Yet, it is ingrained in the DNA of the American identity.

We need our future citizens to understand the inextricable connection between the past, the present, and the future.

Leaders of the American Revolution spoke about freedom from British tyranny. However, in order to understand freedom, one must understand slavery.

A critical exploration of slavery shows why the American Revolution was important. It also shows the unfinished business of the revolution.

Besides, students will learn about slavery (and its legacy – racism) one way or another.

It’s being discussed on social media and found throughout popular culture.

In order for students to grow to be active members of a diverse society, they must be able to comprehend the evolving understanding of who is American and how that has and continues to be center to discussions about our collective identity and future.

When discussing the lives of enslaved individuals, what aspects should teachers include?

Some of the key aspects around the topic of slavery that we find most beneficial:

- Slavery was a legal means of defining a group of people, based on race, as being chattel property and inferior to another group.

- Despite the laws, enslaved individuals were active in challenging the prevailing thoughts on freedom and equality.

- Enslaved women endured unique circumstances as compared to enslaved men.

- Although slavery was the prevailing practice, there were many free people who vehemently opposed the practice. Also, there were slave owners who evolved to oppose slavery and actively manumitted enslaved peoples.

- Although slavery was most prevalent in the south, the north was complicit in its continuation (i.e Rhode Island’s shipbuilding industry producing slave ships). See Complicity: How the North Promoted, Prolonged, and Profited from Slavery by Anne Farrow.

- The legacy of slavery is racism.

When teaching a highly-diverse group of upper elementary students, what are the best ways to make all students feel comfortable and included in the discussion of slavery? How would you approach students who are angry and bitter about the institution of slavery?

Set ground rules for discussion. The ones I’ve commonly used (gained from the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience) are:

- Listen fully and respectfully

- “Share the air” – allow all voices to be heard

- Speak only for yourself, not as a representative of any group.

- Seek first to understand – ask questions to clarify, not to debate.

- Stay open – we’re all free to change our minds.

- Make an effort to suspend your own judgment as you listen to others.

This sets the stage for a dialogue that can be used to balance between what we want to students to know, to feel, and what we want them to do after the lesson. I’m not talking about prescribing outcomes, but channeling the lesson to accomplish these objectives.

For students who have anger toward the content, it would be good to have a conversation about how the content makes them feel.

Encourage them to use words, or images, to describe how they feel. I met a teacher who successfully had her students draw or find images that reflect how the subject makes them feel and why. I always thought this was a good tactic.

Listen twice as much as we speak.

How do you answer the questions that students ask about the fact that our founding fathers proclaimed that “all men are created equal” while holding enslaved individuals in bondage?

It is clear that many believed that “all men are created equal” while also believing that all men did not need to be treated equally. This is seen in the introductory language of the Virginia Declaration of Rights adopted on June 12, 1776:

THAT all men are by nature equally free and independent, and have certain inherent rights, of which, when they enter into a state of society, they cannot, by any compact, deprive or divest their posterity; namely, the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.

The words “when they enter into a state of society” was added to ensure that there was an understanding that slaves were not a part of civil society.

This speaks to a larger belief that Africans and their descendents were viewed as being inferior. This belief of enslaved (and free Blacks) being inferior is also seen in Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia Query XIV where he stated,

I advance it therefore as a suspicion only, that the blacks, whether originally a distinct race, or made distinct by time and circumstances, are inferior to the whites in the endowments both of body and mind.

It is also clear that freeing the enslaved compromised the union of the colonies, later states.

For example, Thomas Jefferson initially included a passage attacking slavery in his draft of the Declaration of Independence which initiated the most intense debate among the delegates gathered at Philadelphia in the spring and early summer of 1776.

Jefferson’s passage on slavery was replaced with a more ambiguous passage about King George’s incitement of “domestic insurrections among us.” Decades later, Jefferson blamed the removal of the passage on delegates from South Carolina and Georgia and Northern delegates who represented merchants who were at the time actively involved in the Trans-Atlantic slave trade.

In your opinion, what is the best way we can use historical concepts to help students become UPstanders instead of bystanders?

I believe that the lesson needs to be grounded in the forensic evidence, or the primary sources and objects.

Then, insert secondary sources, or what I call interpretations, which help reflect differing interpretations of slavery.

It is imperative that we no longer use the words of slave owners as the definitive proof for understanding slavery. We’ve got to dig deeper and also look at slave narratives, like Briton Hammon, Olaudauh Equiano, and many others. (UNC’s Documenting the American South has quite a few accessible online).

Lastly, with this being such a polarizing subject, it’s imperative that the learning environment is designed for discovery and exploration. Teachers can help guide students to understand the past, make meaning of it, and see why this topic is so relevant today as we continue to struggle with the question, “Who is American?” and “How has this changed over time?”

Richard Josey is the President and Principal Consultant for Collective Journeys LLC, a consultation service for museums and historical organizations interested in producing inclusive historical narratives. Prior to building this small practice, Richard spent 20 years developing education-based programs at The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation and the Minnesota Historical Society. Josey began his career in 1985 as a history interpreter portraying African-Virginian experiences in the 17th and 18th centuries, including slavery. In 2001, he became a manager of interpretive programs and soon after supervised staff and developed programs that cross class, race and gender boundaries. In September 2012, Josey became the Manager of Programs at the Minnesota Historical Society. As the manager of programs, Josey directed the development of interpretive programs and provided administrative supervision and policy support for the Society’s network of 26 historic sites and museums. Josey’s personal credo speaks to the overall purpose of Collective Journeys LLC – to encourage all people to consider the question “What Kind of Ancestor Do I Want To Be?”

Email: richard.josey@collectivejourneys.org

Website: www.collectivejourneys.org